This article outlines a series of steps to complete before, during and after lockdowns to minimize anxiety and trauma. The Navigating Lockdowns series also contains shorter articles with key takeaways for administrators, teachers and parents.

“Code Red,” comes the announcement over the intercom. Throughout the school, students and teachers spring into action.

Teachers frantically wave stray students into the nearest classrooms. Locks click. Lights shut off. Students construct barricades out of desks and squeeze into hiding places. The building is silent.

In schools across the country, this scene is repeated several times each year. Most often, it’s a drill. Sometimes, it’s in response to a reported threat, a nearby danger or an armed individual on campus. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 95% of public schools now practice silently hiding from an imaginary gunman.

Imaginary or not, these drills trigger anxiety and even trauma for students. Students have reported fainting, vomiting and nightmares in response to these jarring experiences. Still, many schools and districts view these drills as a necessary safety measure.

So, we must ask ourselves an unusual question: How do we prepare teachers and children for a life or death situation and optimal learning at the same time? How can we ease the anxiety and trauma of these events and help children return to learning?

The Effects of Active Shooter Drills

Recently, active shooter drills have ramped up in intensity. Some schools have gone so far as to fire blanks at students, simulate gunshot sounds, and use smoke and fake blood.

In other cases, students aren’t informed that the lockdown is a drill. They send what they believe are final goodbyes to their parents via text message. In the days that follow these drills, many students are afraid to go to school. Those who do go to school struggle to focus on academics when their minds are on danger and death.

Here, it’s important to understand how the brain works. The more you believe you are in danger, the more traumatized you will be. Practicing procedures is considered important, but we can prepare children for the worst without having them experience the worst. Simulating a realistic active shooter scenario is not necessary. In addition, students should be informed if the lockdown is a drill.

Even when these best practices are followed, students may experience anxiety and trauma. Having seen these events unfold on the news, even drills can feel all too real for students.

Children who are regularly exposed to frightening circumstances may experience depression, poor sleep, ongoing anxiety and worsening academic performance. This is not the nurturing learning environment we want for our students.

Ultimately, gun laws may or may not change. Mental health services may or may not arrive. But we—teachers, administrators, and parents—we will be there. And there are steps we can take right now.

What to Do Before a Lockdown Drill

Before a lockdown drill occurs, the two key areas of focus should be: 1) Practice the physical procedures so teachers and students know what to do, and 2) Teach self-regulation so the stress response doesn’t take over and make recovery impossible.

Middle school principal Diane Phelan explains that it’s vital to remind teachers of emergency procedures and what to do during drills. “Otherwise,” she says, “You’ll create anxiety for the teachers that will trickle down to the children. Whatever the teacher’s reaction is, the kids will respond to that.”

1. Have a visual routine for lockdown procedures

It’s helpful to post a step-by-step visual routine for lockdown procedures. Children’s brains encode information in pictures. Visual routines allow every child to embed the information in their minds, and they’re also a useful reminder for teachers. Ideally, use photos of your students completing each step. If that’s not an option, find pictures online.

Hannah Mercer, a sixteen-year-old junior in high school, says, “As a student, I thrive on having a plan and knowing what to do if an emergency situation happens.” Preparation prevents panic.

2. Infuse self-regulation into school culture

Self-regulation is the ability to regulate your thoughts, feelings and actions in service of a goal. It is essential for every phase of a competent lockdown.

Humans are genetically wired to survive. When the survival system is activated, the higher centers of the brain (where problem-solving and learning occur) shut down. They’re not needed. All reasoning goes out the window.

We must teach students to calm themselves enough to come from the lower centers back up to the higher centers. Only then can they make wise choices during a lockdown and continue learning when it’s over.

Start your self-regulation program by teaching S.T.A.R. and Wishing Well.

S.T.A.R. and Wishing Well

S.T.A.R. stands for Smile, Take a deep breath, And Relax. It involves three deep belly breaths that disengage the stress response. Breathe in through your nose (belly going out) and out through your mouth (belly going in), exhaling longer than you inhale.

Wishing Well is a way to calm ourselves while offering compassion to others. To Wish Well: 1) Put your hands over your heart, 2) Take a deep breath in, 3) Pause and picture something precious in your mind, and 4) Breathe out while opening your arms and sending loving thoughts to the person you are wishing well.

Begin practicing S.T.A.R. and Wishing Well now. First, teach the skills when students are calm. Then, in moments of distress, encourage students to respond by breathing, being a S.T.A.R., and Wishing Well. Model these skills yourself too.

By doing so, you’ll keep the climate calm and teach valuable skills that students can use during lockdowns or other times of stress.

3. Practice, practice, practice procedures

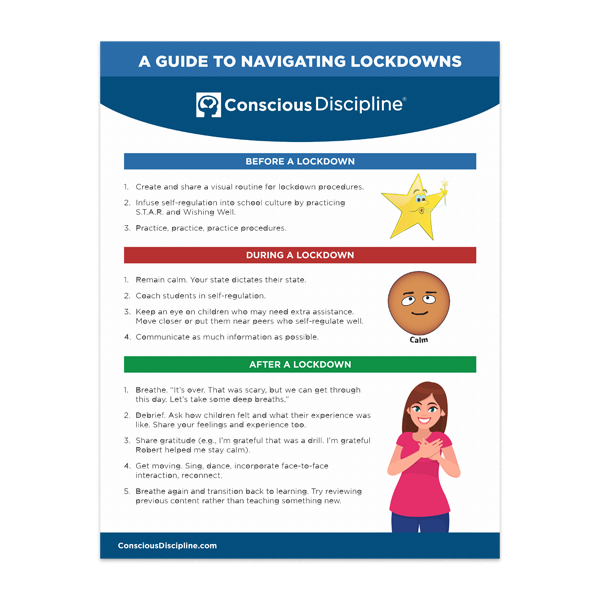

At the beginning of the school year, practice lockdown procedures informally in your classroom. Gently explain each step of the process as you walk through it with your students. The more you prepare your students, the less alarmed they’ll feel when they hear, “Code Red,” over the intercom. Free Printable: Download the Guide to Navigating Lockdowns for reminders on how to establish safety and reduce anxiety before, during and after lockdown drills.

Free Printable: Download the Guide to Navigating Lockdowns for reminders on how to establish safety and reduce anxiety before, during and after lockdown drills.

What to Do During a Lockdown Drill

During the lockdown drill, everything happens quickly. You’ll also need to remain mostly silent. Still, there are a few simple steps you can take to keep the classroom environment as calm as possible.

1. Remain calm

In times of crisis or stress, your students watch your face and your nonverbal communication. They will take their cues about how to respond to the situation from you. Your state dictates their state.

If you want students to remain calm and regulate their emotions, you must lead by example. For some educators, lockdowns can be stressful or triggering. If this is the case for you, take a moment to take several deep breaths and remind yourself, “I’m safe. Keep breathing. I can handle this.”

2. Coach students in self-regulation

Once you’re regulated, coach your students through the same process to help them remain calm. Quietly lead them through some deep breathing exercises, reminding them of S.T.A.R. and Wishing Well.

Encourage them to manage their thoughts with the mantra mentioned above: “I’m safe. Keep breathing. I can handle this.” You can even write the mantra on your board if you’re unable to speak. This calming phrase can replace the inner panic some students may feel. Assure the students that you will keep them safe.

3. Keep an eye on children who may need extra assistance

You’re probably aware of some students who may need extra support during lockdowns. You can also pay attention to your students’ facial expressions and eyes to track how they’re feeling.

Move closer to students who need extra assistance. Alternatively, put them next to peers who can self-regulate well. Simply feeling calm energy helps students begin to calm themselves.

4. Communicate as much information as possible

Anxiety manifests itself in “What if…?” questions. It sends the message, “You don’t know enough. Get more information.”

The more information you can share, the lower your students’ anxiety levels will be. Of course, some information may be confidential. Share as much as you’re able.

What to Do After a Lockdown Drill

After a lockdown drill, you want to get children back to class and learning. For this to occur, they can’t be in a trauma state. They must be in a calm state where they can move past the experience and integrate it.

For many students, this process takes time. Sixteen-year-old Hannah Mercer recalls an incident when an individual with a gun was spotted in her school’s parking lot. The threat was quickly resolved, but the fear remained. It didn’t help that there was no reassurance or reflection afterward.

Hannah says, “Twenty-four hours after sitting in a classroom thinking our lives were in danger, we were expected to sit in the same class and take in content and pass a test at the end of the week. There’s no way.”

Soothe nerves, reduce trauma and transition back to learning with the following five-step process. If the lockdown was not merely a drill, you’ll spend more time on each step.

1. Breathe

Say something like, “It’s over. That was scary, but we can get through this day. Let’s take some deep breaths.”

Lead the children in S.T.A.R. breathing and wishing others well.

2. Debrief

Take time to discuss the experience as a class. Ask questions like:

- How was that for you?

- What was your experience?

- What were you feeling?

Share your experience and your feelings too. During this time, children may have several “What if…?” questions. Answer these questions until your students feel comfortable and calm.

For children who have already experienced trauma, more time is typically needed to reflect and decompress. Fifth grade teacher Kristin Abel shares, “These children may look like they’re daydreaming or spacing out. I make a note to take an extra moment to connect with them. Simply talking won’t bring them back. They need eye contact, a touch on the shoulder, something more.”

3. Share gratitude

End your debriefing by sharing gratitude:

- I’m grateful that was a drill.

- I’m grateful I sat next to Robert. He helped me stay calm.

- I’m grateful I was able to text my mom and she texted me back.

- I’m grateful the teacher stayed calm so we knew we were safe.

4. Get moving

Next, it’s important to get some energy moving and generate positive emotions so you can upgrade to a higher brain state.

Incorporate singing, dancing, or movement. Have children speak to partners face to face. Take a few minutes to reconnect as a class.

5. Transition back to learning

Finish up with more deep breathing before transitioning back to learning. Now is not the best time to introduce new content. Do something light, playful and interactive. Perhaps play a game to review previously taught content.

Sometimes, you may feel that these activities are a waste of time. Remember that after a lockdown, helping your students integrate a potentially traumatic experience is more important than academic content.

Additionally, many students are not in the optimal state for understanding or retaining new content. Taking the time to return to the higher centers will make anything you teach next much more effective.

Final Thoughts: Navigating Lockdowns

In addition to these practices before, during and after a lockdown, work on building connections with your students. Create a classroom or school environment where children feel safe, loved and accepted. In this School Family environment, the practices described here make a far greater impact. We also get the opportunity to reach the most challenging children early in life.

Today, lockdown drills are an unfortunate reality. Effectively navigating lockdowns requires teaching procedures to children to keep them safe, but focusing on procedures alone is not enough. In fact, it may be harmful. Teach children self-regulation, help them feel safe and calm, and allow time to debrief and regain composure after these scary situations.

We must do more, and we can do more. We don’t have to wait for gun laws, metal detectors or funding for security. We can do this right now.