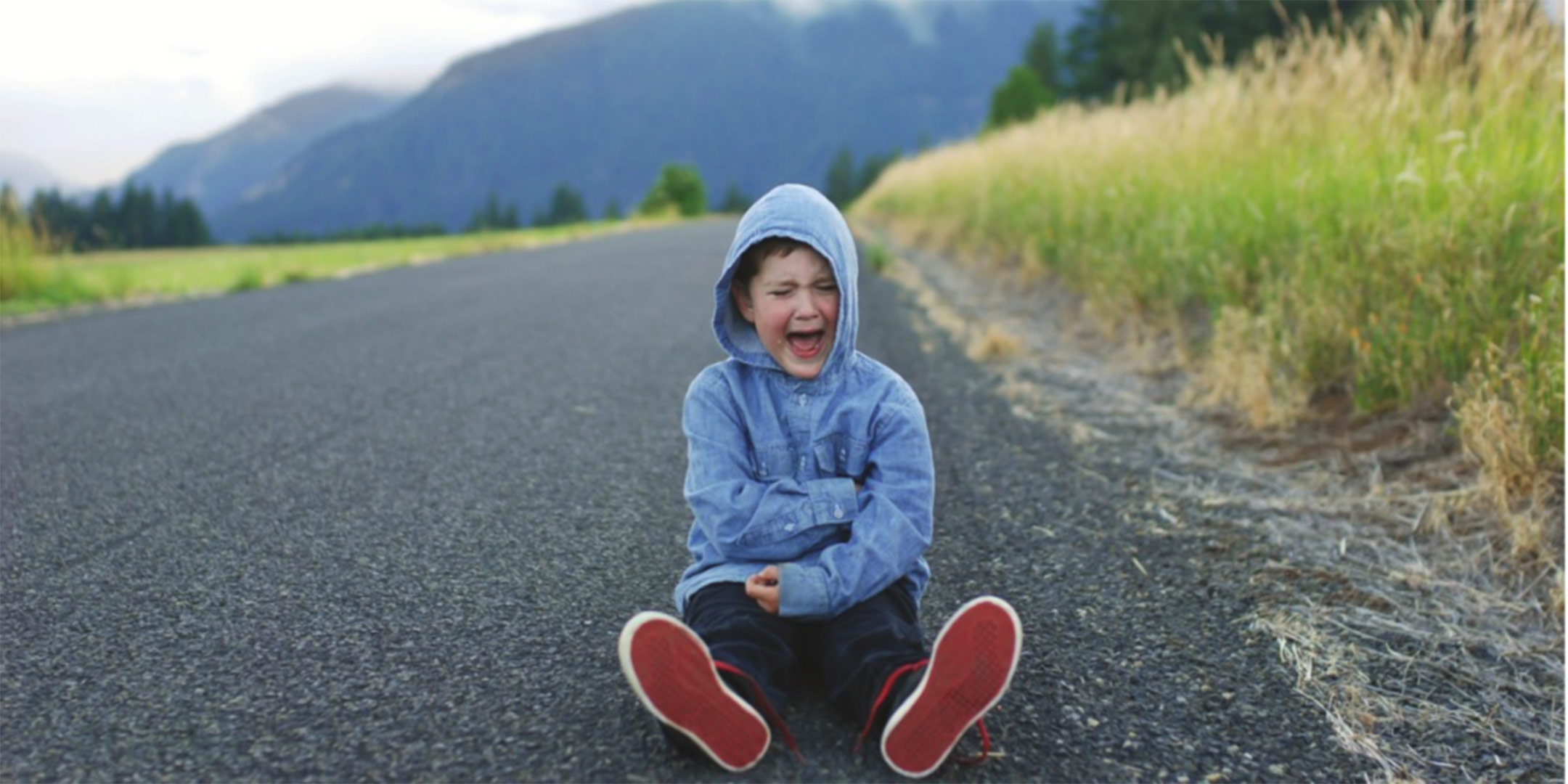

Problem behavior is always a call for help. It is the child’s attempt to express the need to be taught new coping strategies to handle upset or disappointment safely. However, we often see the problem behavior as intentional and something that can be controlled.

This judgment interferes with seeing the behavior as a skill deficit like we see math and reading struggles. Judging the behavior prevents us from identifying the “root cause” of the problem so that we can find an intervention that teaches a missing skill or a replacement behavior.

We must understand how the brain operates in times of stress so we can soothe the lower centers of the brain (using rituals, breathing, and movement). This understanding must happen before providing an intervention strategy. Ignoring the problem behavior will only increase the likelihood that it will continue or increase in severity. Using strategies to soothe the lower centers of the brain will provide a way for the child to calm down and learn new strategies that will help them become consciously aware of the behavior and how to do it differently next time.

“What we have to teach in the curriculum is NOT more important than listening to what the brain NEEDS to be able to learn the curriculum.” ~ Jenny Barkac

When viewing academic challenges, educators look at the lack of academic skills as a skill deficit that may need intervention or extra time to practice a certain concept. It is viewed as a missing skill that may need a differentiated approach to meet the need of the student. It is not dealt with using punishment or frustration but with empathy for the struggling that the student has to deal with while learning the missing skills. Teaching these missing academic skills can take time and may require an intervention to teach the specific skill that is missing. Educators view this as an opportunity to support the student with missing skills and an acceptable way to meet individual needs. The child may remain in an intervention all year. As long as individual progress is being made the intervention is viewed as successful. For example: If a child is struggling reading fluently it is important to provide an intervention that will support that specific deficit and build the missing skill for increased fluency. Knowing the specific skill that is missing is important for understanding how to support the student and increase proficiency. Frequent practice time is offered to this student to increase understanding on how to apply the new skill.

This same concept can be used to support problem behavior. Viewing the behavior deficit as a missing skill and identifying the underdeveloped executive skill will provide strategies for specific interventions. These interventions will teach the student how to change the problem behavior and recognize how to regulate the emotions related to this deficit. This awareness will offer the student an opportunity to learn to manage upset and frustration differently and information on how to get his/her needs met safely.

During behavior struggles the child is using the only coping strategy that they know. It is not our job to get rid of the behavior but to teach them a healthy coping strategy to use to manage upset or handle disappointment that will replace the one that is not safe. This will take time and practice during a “non-conflict time”. A great time to teach coping strategies to the whole class is during morning meeting or circle time. Most students are ready to learn and are willing to practice during this time, or role-play a scenario that may have come up the day before. Teaching and practicing when it is not a stressful moment allows the students to retain the information and store it for later recall. Usually we are trying to teach them what to do differently during the conflict when they are not able to access those reasoning skills. We allow time every day to practice math and reading skills, we need to incorporate conflict resolution skills and discussions of what to do when things don’t go as planned, daily or they won’t be able to access these skills when they need them later.

When deciding how to solve a behavior problem, think about what you would do if it was a math or reading problem. Remember to use the many academic teaching strategies that work such as pre-teach, re-teach, small groups, proximity, and class meetings. Approach the problem behavior the same way with pre-teaching what they may need more of (ex: finding a place at carpet), allow them time to practice the new strategy before they need it, and then coach them as they try to do it with the new skills you have taught them. Remember that the brain seeks patterns so the brain is used to recalling the unsafe behavior first, the child may need help remembering the new skill and positive feedback as they attempt to do it differently. Retraining the brain is a process just like teaching a new academic skill can be a process. Your perception of the behavior will focus your intention during this process so remember to treat this process like any other academic learning opportunity. Notice what the child can do and encourage them, as they want to be successful.